This is probably the most significant change coming to the framework since the release of Angular v2 many years ago.

A new feature called Signals is being prototyped in Angular, and we can follow the entire discussion on GitHub.

Where do signals come from?

They are the answer from the Angular team to several different requests from the developer community over the years, more specifically:

- Being able to use Observables with

@Input

- Being able to use Angular without Zone.js to have more control over change detection.

- Having state management built-in with the framework so we don’t need libraries like NgRx or NgXs anymore.

- Being able to use Angular in a reactive way without relying on RxJs.

In other words, Signals will be a clear and unified model for how data flows through an application and will work without any dependency (no RxJs, Zone, or other third-party library needed).

Will we have to change everything in our apps?

No, because the Angular team has communicated that:

- Signals will be optional, and the current way of working with Angular will remain in place.

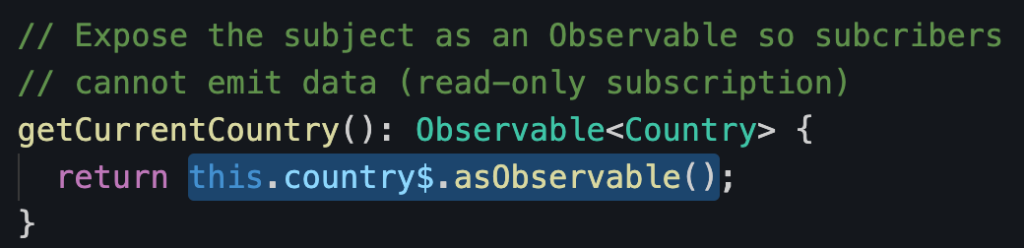

- Signals will provide ways to play nicely with RxJs (a Signal can be turned into an Observable and vice-versa)

What will signals look like?

It’s still early to have a definite API. We’re not 100% sure what signals will look like, but the early prototype API looks like this:

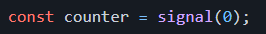

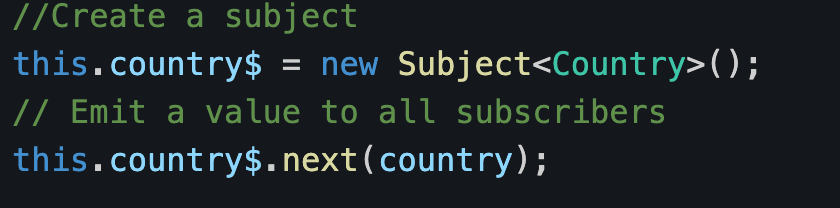

Creating a signal with a default value (of 0 in this example)

The above line of code would be very much like doing const counter = new BehaviorSubject(0);

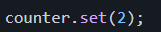

Setting a new value to a signal

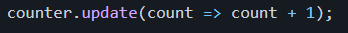

Updating a value derived from the current value

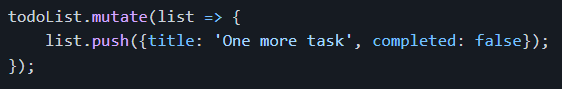

Updating a value within a signal (mutation of the internal state)

Displaying the value of a signal in an HTML template or Typescript code

The above would be the equivalent of counter | async when using RxJs. The nice thing is that with Signals, there will be no more .subscribe() and .unsubscribe().

If you want to dive into more details, here is the documentation of the current prototype. Again, this is still early and I would not expect Signals to become fully available before Angular 17 or 18, but this is very exciting nevertheless!