Angular 17 is available, and we already covered its new optional control-flow syntax. Today, let’s cover the new option to fully customize lazy-loading with Angular using @defer.

What’s great about @defer is that it does not rely on the Angular router anymore. You can lazy-load any standalone component anywhere, anytime, and on your terms, as you can decide the trigger to load that component.

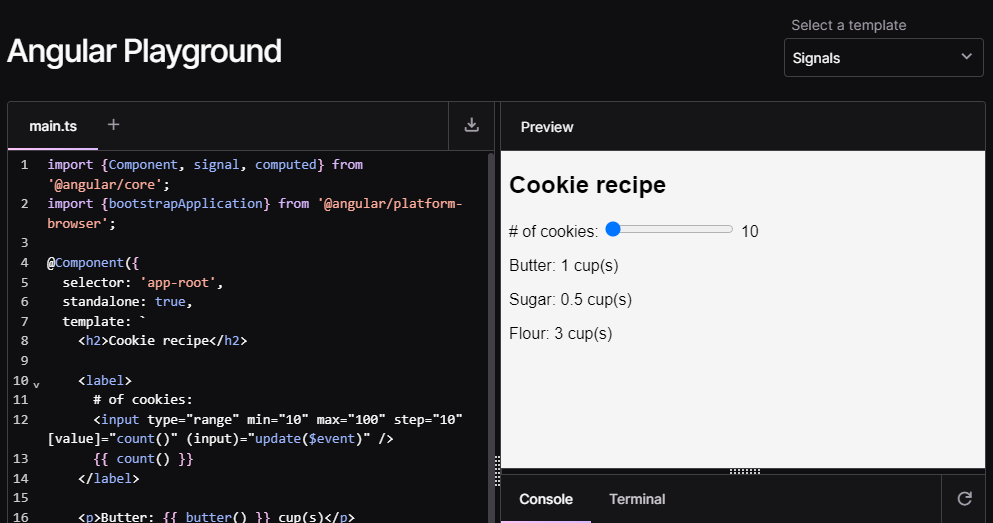

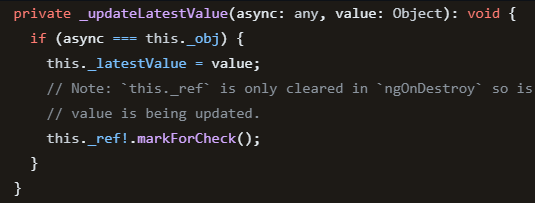

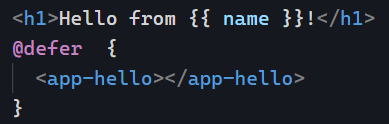

Let’s start with a basic example:

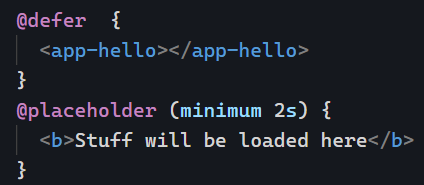

The above code will load the HelloComponent as soon as the browser is idle, which means it’s done loading everything else. While that is happening, we can decide to display a placeholder, and in my case, I decided that such a placeholder would be displayed for a minimum of 2 seconds no matter what. You can use seconds (s) or milliseconds (ms) as a time unit:

You can see the above code in action here on Stackblitz. Note that the Angular Language service was updated accordingly, so VS Code (Stackblitz is a web-based VS code), Webstorm, and other IDEs already know about the new @defer syntax and do proper highlighting of it!

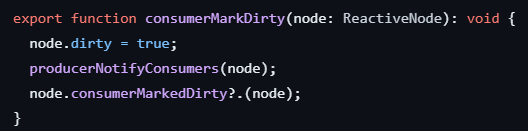

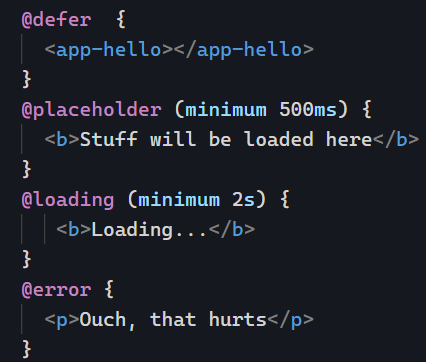

We can also specify a loading template and an error template, all customizable with a minimum amount of time during which we would display those templates (example on Stackblitz here):

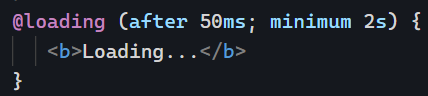

I used “big” numbers to see the different states in my examples. Note that @loading supports an “after ” option only to show the loading template if loading takes more than a certain amount of time, so you don’t have to display anything if the component loads quickly. Both parameters are optional:

These are the different new blocks available with @defer. Tomorrow, we’ll look at the various possible triggers.