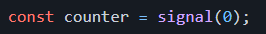

As Angular developers, we use and create services fairly often. So, in today’s post, let’s demystify the following syntax and see what the different options for it are:

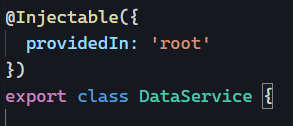

When a service is provided in the root injector (providedIn: 'root'), it means that such a service can be injected into any component of your application, and that service will be a singleton shared by all consumers in your application.

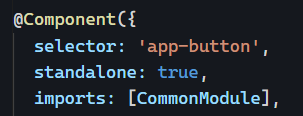

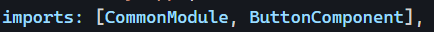

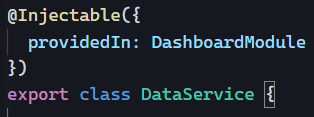

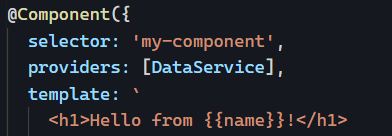

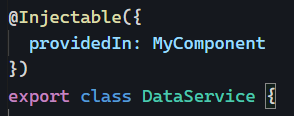

If we want to restrict the scope of a service, we can provide it in a module or a component instead of the root injector. The syntax looks like this – we use the class name of the targeted module or component:

When a service is provided in a module, only the components/directives/pipes/services of that module can inject that service. However, when provided in a component, that component and its children can inject that service.

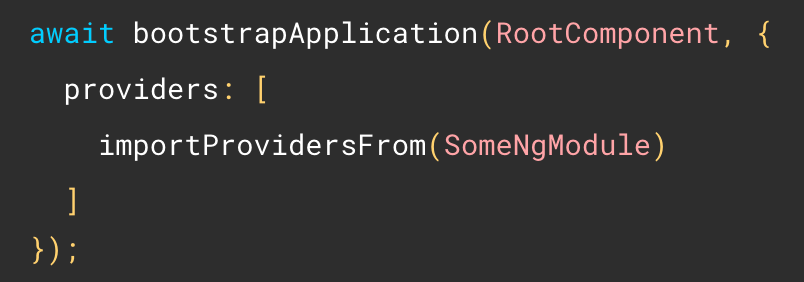

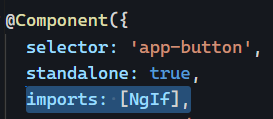

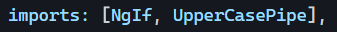

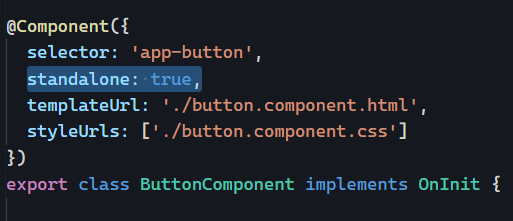

From a syntax standpoint, it’s also important to mention that using providedIn is equivalent to doing the following in a component or a module:

The above code is equivalent to the following:

So you only need one or the other; both would be redundant.

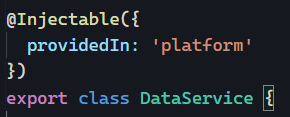

Finally, there is another option available: platform.

The service would be injectable into any Angular app in the current browser tab. It’s a rare use case, but if you’re running multiple Angular applications on the same page and want to share a service between these applications, platform is what you need.

For more information, you can read that post of mine that covers all these options (note: providedIn: 'any' used to be an option but is now deprecated, which is why I didn’t mention it)