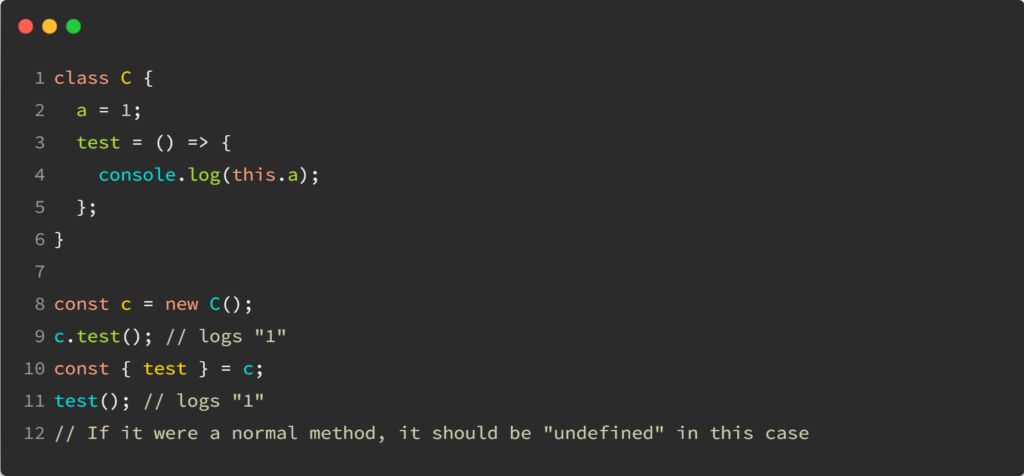

We use dependency injection daily to inject services in our Angular “objects,” such as components, directives, pipes, and other services.

Angular does offer other kinds of injectables, though, and one of those is the ElementRef. Its primary purpose is to give us direct access to the native DOM element of a component or a directive.

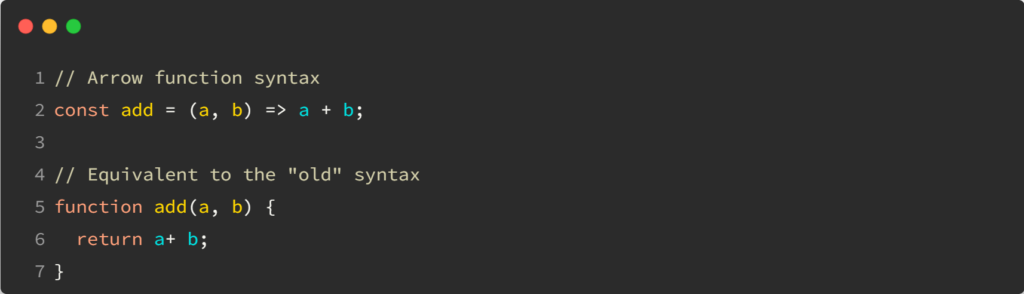

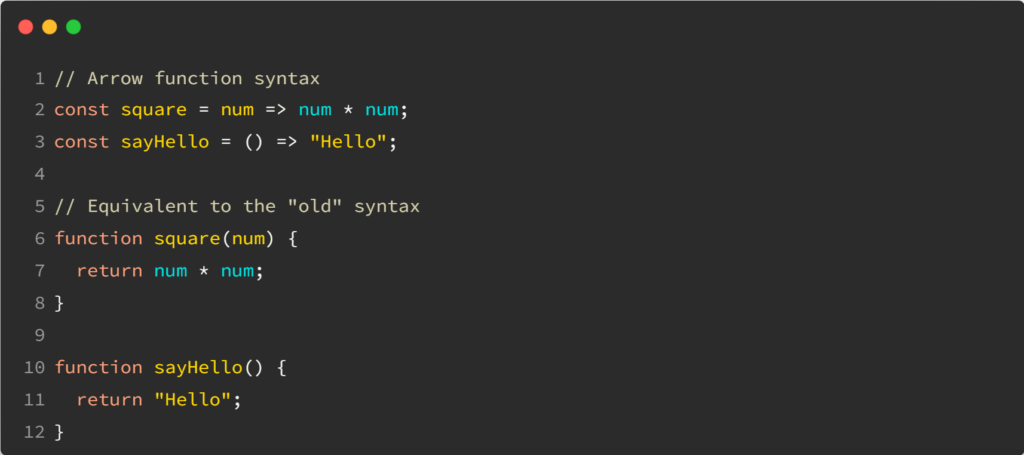

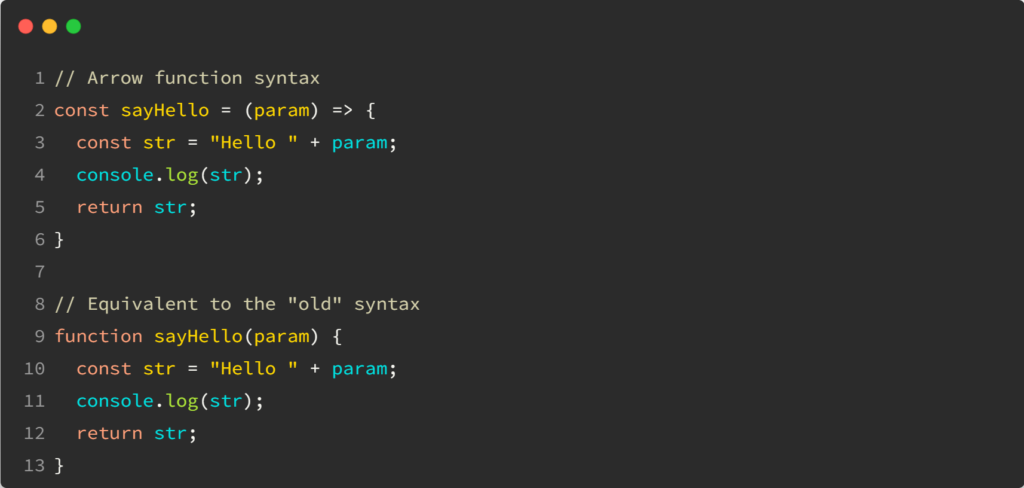

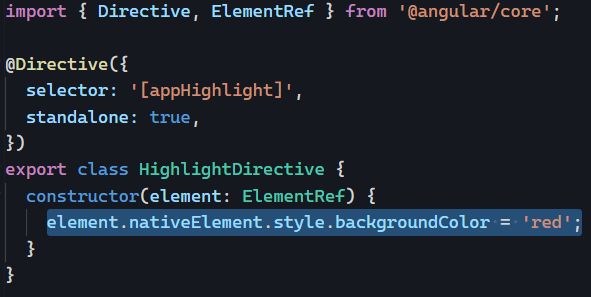

Here’s a code example (you can test it in Stackblitz here):

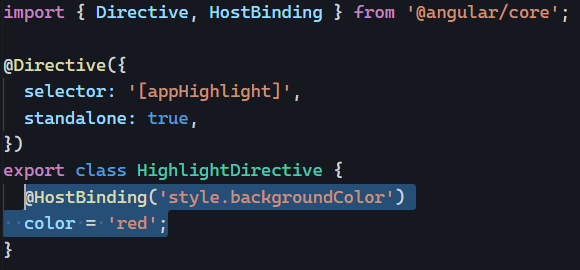

The above code changes the background color of the HTML element to red. It’s important to note that the above implementation is not ideal. We should use Angular data bindings for such a use case, which are a lot more readable (code example in Stackblitz here):

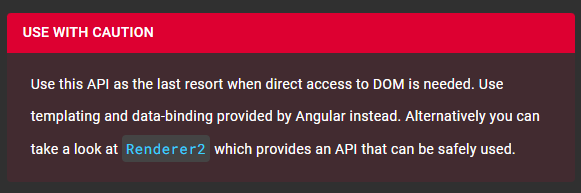

The Angular team doesn’t recommend using this API either:

So when should we use ElementRef? Just like markForCheck, it’s a last resort option, and we should use it when everything else fails. The only use case I would consider for ElementRef is when I have to interact with a non-Angular 3rd-party library, such as a chart or a map library, after carefully checking that Angular wrappers are not available on npm (or such wrappers do not pass my tests for good, reliable dependencies)